How Is Hepatitis C Transmitted

Hepatitis C infection is treated with antiviral medications intended to clear the virus from your body. The goal of treatment is to have no hepatitis C virus detected in your body at least 12 weeks after you complete treatment. Risk factors for hepatitis C and care in the VA, February 2016 Hepatitis C Virus Transmission An overview of HCV transmission through blood, injection drug use, sexual activities and other modes of transmission.

| Hepatitis C | |

|---|---|

| Electron micrograph of hepatitis C virus from cell culture (scale = 50 nanometers) | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Typically none[1] |

| Complications | Liver failure, liver cancer, esophageal and gastric varices[2] |

| Duration | Long term (80%)[1] |

| Causes | Hepatitis C virus usually spread by blood-to-blood contact[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood testing for antibodies or viral RNA[1] |

| Prevention | Clean needles, testing donated blood[4] |

| Treatment | Medications, liver transplant[5] |

| Medication | Sofosbuvir, simeprevir[1][4] |

| Frequency | 143 million / 2% (2015)[6] |

| Deaths | 496,000 (2015)[7] |

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that primarily affects the liver.[2] During the initial infection people often have mild or no symptoms.[1] Occasionally a fever, dark urine, abdominal pain, and yellow tinged skin occurs.[1] The virus persists in the liver in about 75% to 85% of those initially infected.[1] Early on chronic infection typically has no symptoms.[1] Over many years however, it often leads to liver disease and occasionally cirrhosis.[1] In some cases, those with cirrhosis will develop serious complications such as liver failure, liver cancer, or dilated blood vessels in the esophagus and stomach.[2]

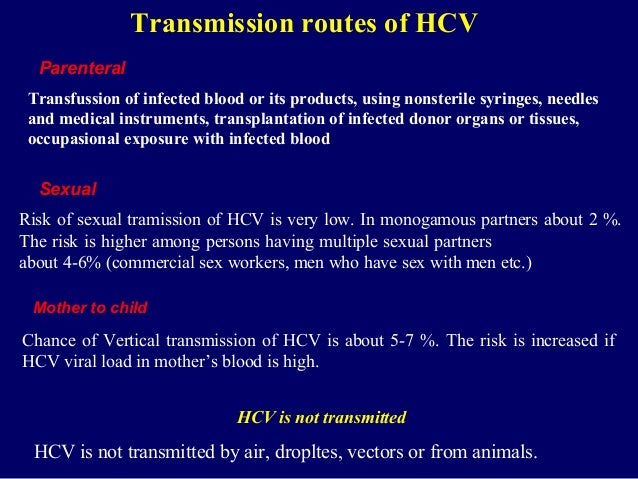

Hepatitis C is transmitted primarily by contaminated blood parenterally, and is often associated with transfusion and intravenous drug abuse. However, in a significant number of cases, the source of hepatitis C infection is unknown.

HCV is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact associated with intravenous drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment, needlestick injuries in healthcare, and transfusions.[1][3] Using blood screening, the risk from a transfusion is less than one per two million.[1] It may also be spread from an infected mother to her baby during birth.[1] It is not spread by superficial contact.[4] It is one of five known hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E.[8] Diagnosis is by blood testing to look for either antibodies to the virus or its RNA.[1] Testing is recommended in all people who are at risk.[1]

There is no vaccine against hepatitis C.[1][9] Prevention includes harm reduction efforts among people who use intravenous drugs and testing donated blood.[4] Chronic infection can be cured about 95% of the time with antiviral medications such as sofosbuvir or simeprevir.[1][4]Peginterferon and ribavirin were earlier generation treatments that had a cure rate of less than 50% and greater side effects.[4][10] Getting access to the newer treatments however can be expensive.[4] Those who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer may require a liver transplant.[5] Hepatitis C is the leading reason for liver transplantation, though the virus usually recurs after transplantation.[5]

An estimated 143 million people (2%) worldwide are infected with hepatitis C as of 2015.[6] In 2013 about 11 million new cases occurred.[11] It occurs most commonly in Africa and Central and East Asia.[4] About 167,000 deaths due to liver cancer and 326,000 deaths due to cirrhosis occurred in 2015 due to hepatitis C.[7] The existence of hepatitis C – originally identifiable only as a type of non-A non-Bhepatitis – was suggested in the 1970s and proven in 1989.[12] Hepatitis C infects only humans and chimpanzees.[13]

- 1Signs and symptoms

- 3Transmission

- 4Diagnosis

- 6Treatment

- 6.1Medications

- 11Special populations

- 12Research

Signs and symptoms

Acute infection

Hepatitis C infection causes acute symptoms in 15% of cases.[14] Symptoms are generally mild and vague, including a decreased appetite, fatigue, nausea, muscle or joint pains, and weight loss[15] and rarely does acute liver failure result.[16] Most cases of acute infection are not associated with jaundice.[17] The infection resolves spontaneously in 10–50% of cases, which occurs more frequently in individuals who are young and female.[17]

Chronic infection

About 80% of those exposed to the virus develop a chronic infection.[18] This is defined as the presence of detectable viral replication for at least six months. Most experience minimal or no symptoms during the initial few decades of the infection.[19] Chronic hepatitis C can be associated with fatigue[20] and mild cognitive problems.[21] Chronic infection after several years may cause cirrhosis or liver cancer.[5] The liver enzymes are normal in 7–53%.[22] Late relapses after apparent cure have been reported, but these can be difficult to distinguish from reinfection.[22]

Fatty changes to the liver occur in about half of those infected and are usually present before cirrhosis develops.[23][24] Usually (80% of the time) this change affects less than a third of the liver.[23] Worldwide hepatitis C is the cause of 27% of cirrhosis cases and 25% of hepatocellular carcinoma.[25] About 10–30% of those infected develop cirrhosis over 30 years.[5][15] Cirrhosis is more common in those also infected with hepatitis B, schistosoma, or HIV, in alcoholics and in those of male gender.[15] In those with hepatitis C, excess alcohol increases the risk of developing cirrhosis 100-fold.[26] Those who develop cirrhosis have a 20-fold greater risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. This transformation occurs at a rate of 1–3% per year.[5][15] Being infected with hepatitis B in addition to hepatitis C increases this risk further.[27]

Liver cirrhosis may lead to portal hypertension, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen), easy bruising or bleeding, varices (enlarged veins, especially in the stomach and esophagus), jaundice, and a syndrome of cognitive impairment known as hepatic encephalopathy.[28] Ascites occurs at some stage in more than half of those who have a chronic infection.[29]

Extrahepatic complications

The most common problem due to hepatitis C but not involving the liver is mixed cryoglobulinemia (usually the type II form) — an inflammation of small and medium-sized blood vessels.[30][31]Hepatitis C is also associated with the autoimmune disorder such as Sjögren's syndrome, lichen planus, a low platelet count, porphyria cutanea tarda, necrolytic acral erythema, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, diabetic nephropathy, autoimmune thyroiditis, and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.[32][33] 20–30% of people infected have rheumatoid factor — a type of antibody.[34] Possible associations include Hyde's prurigo nodularis[35] and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.[20]Cardiomyopathy with associated abnormal heart rhythms has also been reported.[36] A variety of central nervous system disorders has been reported.[37] Chronic infection seems to be associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.[9][38] People may experience other issues in the mouth such as dryness, salivary duct stones, and crusted lesions around the mouth.[39][40][41]

Occult infection

Persons who have been infected with hepatitis C may appear to clear the virus but remain infected.[42] The virus is not detectable with conventional testing but can be found with ultra-sensitive tests.[43] The original method of detection was by demonstrating the viral genome within liver biopsies, but newer methods include an antibody test for the virus' core protein and the detection of the viral genome after first concentrating the viral particles by ultracentrifugation.[44] A form of infection with persistently moderately elevated serum liver enzymes but without antibodies to hepatitis C has also been reported.[45] This form is known as cryptogenic occult infection.

Several clinical pictures have been associated with this type of infection.[46] It may be found in people with anti-hepatitis-C antibodies but with normal serum levels of liver enzymes; in antibody-negative people with ongoing elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause; in healthy populations without evidence of liver disease; and in groups at risk for HCV infection including those on hemodialysis or family members of people with occult HCV. The clinical relevance of this form of infection is under investigation.[47] The consequences of occult infection appear to be less severe than with chronic infection but can vary from minimal to hepatocellular carcinoma.[44]

The rate of occult infection in those apparently cured is controversial but appears to be low.[22] 40% of those with hepatitis but with both negative hepatitis C serology and the absence of detectable viral genome in the serum have hepatitis C virus in the liver on biopsy.[48] How commonly this occurs in children is unknown.[49]

Virology

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a small, enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus.[5] It is a member of the genus Hepacivirus in the family Flaviviridae.[20] There are seven major genotypes of HCV, which are known as genotypes one to seven.[50] The genotypes are divided into several subtypes with the number of subtypes depending on the genotype. In the United States, about 70% of cases are caused by genotype 1, 20% by genotype 2 and about 1% by each of the other genotypes.[15] Genotype 1 is also the most common in South America and Europe.[5]

The half life of the virus particles in the serum is around 3 hours and may be as short as 45 minutes.[51][52] In an infected person, about 1012 virus particles are produced each day.[51] In addition to replicating in the liver the virus can multiply in lymphocytes.[53]

Transmission

The primary route of transmission in the developed world is intravenous drug use (IDU), while in the developing world the main methods are blood transfusions and unsafe medical procedures.[3] The cause of transmission remains unknown in 20% of cases;[54] however, many of these are believed to be accounted for by IDU.[17]

Drug use

Intravenous drug use (IDU) is a major risk factor for hepatitis C in many parts of the world.[55] Of 77 countries reviewed, 25 (including the United States) were found to have prevalences of hepatitis C in the intravenous drug user population of between 60% and 80%.[18][55] Twelve countries had rates greater than 80%.[18] It is believed that ten million intravenous drug users are infected with hepatitis C; China (1.6 million), the United States (1.5 million), and Russia (1.3 million) have the highest absolute totals.[18]Occurrence of hepatitis C among prison inmates in the United States is 10 to 20 times that of the occurrence observed in the general population; this has been attributed to high-risk behavior in prisons such as IDU and tattooing with nonsterile equipment.[56][57] Shared intranasal drug use may also be a risk factor.[58]

Healthcare exposure

Blood transfusion, transfusion of blood products, or organ transplants without HCV screening carry significant risks of infection.[15] The United States instituted universal screening in 1992[59] and Canada instituted universal screening in 1990.[60] This decreased the risk from one in 200 units[59] to between one in 10,000 to one in 10,000,000 per unit of blood.[17][54] This low risk remains as there is a period of about 11–70 days between the potential blood donor's acquiring hepatitis C and the blood's testing positive depending on the method.[54] Some countries do not screen for hepatitis C due to the cost.[25]

Those who have experienced a needle stick injury from someone who was HCV positive have about a 1.8% chance of subsequently contracting the disease themselves.[15] The risk is greater if the needle in question is hollow and the puncture wound is deep.[25] There is a risk from mucosal exposures to blood, but this risk is low, and there is no risk if blood exposure occurs on intact skin.[25]

Hospital equipment has also been documented as a method of transmission of hepatitis C, including reuse of needles and syringes; multiple-use medication vials; infusion bags; and improperly sterilized surgical equipment, among others.[25] Limitations in the implementation and enforcement of stringent standard precautions in public and private medical and dental facilities are known to be the primary cause of the spread of HCV in Egypt, the country with highest rate of infection in the world.[61]

Sexual intercourse

Sexual transmission of hepatitis C is uncommon.[10] Studies examining the risk of HCV transmission between heterosexual partners, when one is infected and the other is not, have found very low risks.[10] Sexual practices that involve higher levels of trauma to the anogenital mucosa, such as anal penetrative sex, or that occur when there is a concurrent sexually transmitted infection, including HIV or genital ulceration, present greater risks.[10][62] The United States Department of Veterans Affairs recommends condom use to prevent hepatitis C transmission in those with multiple partners, but not those in relationships that involve only a single partner.[63]

Body modification

Tattooing is associated with two to threefold increased risk of hepatitis C.[64] This can be due to either improperly sterilized equipment or contamination of the dyes being used.[64]Tattoos or piercings performed either before the mid-1980s, 'underground,' or nonprofessionally are of particular concern, since sterile techniques in such settings may be lacking. The risk also appears to be greater for larger tattoos.[64] It is estimated that nearly half of prison inmates share unsterilized tattooing equipment.[64] It is rare for tattoos in a licensed facility to be directly associated with HCV infection.[65]

Shared personal items

Personal-care items such as razors, toothbrushes, and manicuring or pedicuring equipment can be contaminated with blood. Sharing such items can potentially lead to exposure to HCV.[66][67] Appropriate caution should be taken regarding any medical condition that results in bleeding, such as cuts and sores.[67] HCV is not spread through casual contact, such as hugging, kissing, or sharing eating or cooking utensils.[67] Neither is it transmitted through food or water.[68]

Mother-to-child transmission

Mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C occurs in less than 10% of pregnancies.[69] There are no measures that alter this risk.[69] It is not clear when transmission occurs during pregnancy, but it may occur both during gestation and at delivery.[54] A long labor is associated with a greater risk of transmission.[25] There is no evidence that breastfeeding spreads HCV; however, to be cautious, an infected mother is advised to avoid breastfeeding if her nipples are cracked and bleeding,[70] or if her viral loads are high.[54]

Diagnosis

There are a number of diagnostic tests for hepatitis C, including HCV antibodyenzyme immunoassay or ELISA, recombinant immunoblot assay, and quantitative HCV RNApolymerase chain reaction (PCR).[15] HCV RNA can be detected by PCR typically one to two weeks after infection, while antibodies can take substantially longer to form and thus be detected.[28]

Chronic hepatitis C is defined as infection with the hepatitis C virus persisting for more than six months based on the presence of its RNA.[19] Chronic infections are typically asymptomatic during the first few decades,[19] and thus are most commonly discovered following the investigation of elevated liver enzyme levels or during a routine screening of high-risk individuals. Testing is not able to distinguish between acute and chronic infections.[25] Diagnosis in the infant is difficult as maternal antibodies may persist for up to 18 months.[49]

Serology

Hepatitis C testing typically begins with blood testing to detect the presence of antibodies to the HCV, using an enzyme immunoassay.[15] If this test is positive, a confirmatory test is then performed to verify the immunoassay and to determine the viral load.[15] A recombinant immunoblot assay is used to verify the immunoassay and the viral load is determined by an HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction.[15] If there is no RNA and the immunoblot is positive, it means that the person tested had a previous infection but cleared it either with treatment or spontaneously; if the immunoblot is negative, it means that the immunoassay was wrong.[15] It takes about 6–8 weeks following infection before the immunoassay will test positive.[20] A number of tests are available as point of care testing which means that results are available within 30 minutes.[71]

Liver enzymes are variable during the initial part of the infection[19] and on average begin to rise at seven weeks after infection.[20] The elevation of liver enzymes does not closely follow disease severity.[20]

There are reports of negative plasma PCR for the viral genome with positive PCR for the viral genome within peripheral blood monocytes of liver cells.[72] This condition has been termed occult HCV infection and it was first recognized in 2004.[72]

Biopsy

Liver biopsies are used to determine the degree of liver damage present; however, there are risks from the procedure.[5] The typical changes seen are lymphocytes within the parenchyma, lymphoid follicles in portal triad, and changes to the bile ducts.[5] There are a number of blood tests available that try to determine the degree of hepatic fibrosis and alleviate the need for biopsy.[5]

Screening

It is believed that only 5–50% of those infected in the United States and Canada are aware of their status.[64] Testing is recommended for those at high risk, which includes injection drug users, those who have received blood transfusions before 1992,[73] those who have been in jail, those on long term hemodialysis,[74] and those with tattoos.[64] Screening is also recommended in those with elevated liver enzymes, as this is frequently the only sign of chronic hepatitis.[75] Routine screening is not currently recommended in the United States.[15] In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) added a recommendation for a single screening test for those born between 1945 and 1965.[76] In Canada one time screening is recommended for those born between 1945 and 1975.[77]

Prevention

As of 2016, no approved vaccine protects against contracting hepatitis C.[78] A combination of harm reduction strategies, such as the provision of new needles and syringes and treatment of substance use, decreases the risk of hepatitis C in intravenous drug users by about 75%.[79] The screening of blood donors is important at a national level, as is adhering to universal precautions within healthcare facilities.[20] In countries where there is an insufficient supply of sterile syringes, medications should be given orally rather than via injection (when possible).[25]

Treatment

HCV induces chronic infection in 80% of infected persons.[1] Approximately 95% of these clear with treatment.[4] In rare cases, infection can clear without treatment.[17] Those with chronic hepatitis C are advised to avoid alcohol and medications toxic to the liver.[15] They should also be vaccinated against hepatitis A and hepatitis B due to the increased risk if also infected.[15] Use of acetaminophen is generally considered safe at reduced doses.[10]Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are not recommended in those with advanced liver disease due to an increased risk of bleeding.[10]Ultrasound surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is recommended in those with accompanying cirrhosis.[15]Coffee consumption has been associated with a slower rate of liver scarring in those infected with HCV.[10]

Medications

Treatment with antiviral medication is recommended in all people with proven chronic hepatitis C who are not at high risk of dying from other causes.[80] People with the highest complication risk should be treated first, with the risk of complications based on the degree of liver scarring.[80] The initial recommended treatment depends on the type of hepatitis C virus, if the person has received previous hepatitis C treatment, and whether or not a person has cirrhosis.[81]Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) may reduce the number of the infected people.[82]

No prior treatment

- HCV genotype 1a (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (the latter for people who do not have HIV/AIDS, are not African-American, and have less than 6 million HCV viral copies per milliliter of blood) or 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir.[83]Sofosbuvir with either daclatasvir or simeprevir may also be used.[81]

- HCV genotype 1a (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. An alternative treatment regimen of elbasvir/grazoprevir with weight-based ribavirin for 16 weeks can be used if the HCV is found to have antiviral resistance mutations against NS5A protease inhibitors.[84]

- HCV genotype 1b (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (with the aforementioned limitations for the latter as above) or 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. Alternative regimens include 12 weeks of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with dasabuvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir with either daclatasvir or simeprevir.[85]

- HCV genotype 1b (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. A 12-week course of paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir with dasabuvir may also be used.[86]

- HCV genotype 2 (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. Alternatively, 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir can be used.[87]

- HCV genotype 2 (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. An alternative regimen of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir can be used for 16–24 weeks.[88]

- HCV genotype 3 (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir or sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.[89]

- HCV genotype 3 (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, or if certain antiviral mutations are present, 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir (when certain antiviral mutations are present), or 24 weeks of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.[90]

- HCV genotype 4 (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, elbasvir/grazoprevir, or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. A 12-week regimen of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir is also acceptable in combination with weight-based ribavirin.[91]

- HCV genotype 4 (with compensated cirrhosis): A 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, glecaprevir/pibrentasavir, elbasvir/grazoprevir, or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir is recommended. A 12-week course of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with weight-based ribavirin is an acceptable alternative.[92]

- HCV genotype 5 or 6 (with or without compensated cirrhosis): If no cirrhosis is present, then 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir is recommended. If cirrhosis is present, then a 12-week course of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir is warranted.[93]

Chronic infection can be cured about 95% of the time with recommended treatment in 2017.[1][4] Getting access to these treatments however can be expensive.[4] The combination of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir may be used in those who have previously been treated with sofosbuvir or other drugs that inhibit NS5A and were not cured.[94]

Prior to 2011, treatments consisted of a combination of pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin for a period of 24 or 48 weeks, depending on HCV genotype.[15] This produces cure rates of between 70 and 80% for genotype 2 and 3, respectively, and 45 to 70% for genotypes 1 and 4.[95] Adverse effects with these treatments were common, with half of people getting flu-like symptoms and a third experiencing emotional problems.[15] Treatment during the first six months is more effective than once hepatitis C has become chronic.[28] In those with chronic hepatitis B, treatment for hepatitis C results in reactivation of hepatitis B in about 25%.[96]

Surgery

Cirrhosis due to hepatitis C is a common reason for liver transplantation[28] though the virus usually (80–90% of cases) recurs afterwards.[5][97] Infection of the graft leads to 10–30% of people developing cirrhosis within five years.[98] Treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin post-transplant decreases the risk of recurrence to 70%.[99] A 2013 review found unclear evidence regarding if antiviral medication was useful if the graft became reinfetcted.[100]

Alternative medicine

Several alternative therapies are claimed by their proponents to be helpful for hepatitis C including milk thistle, ginseng, and colloidal silver.[101] However, no alternative therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in hepatitis C, and no evidence exists that alternative therapies have any effect on the virus at all.[101][102][103]

Prognosis

Disability-adjusted life year for hepatitis C in 2004 per 100,000 inhabitants <10 15–20 25–30 | 35–40 45–50 75–100 |

The responses to treatment is measured by sustained viral response (SVR), defined as the absence of detectable RNA of the hepatitis C virus in blood serum for at least 24 weeks after discontinuing the treatment,[104] and rapid virological response (RVR) defined as undetectable levels achieved within four weeks of treatment. Successful treatment decreases the future risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by 75%.[105]

Prior to 2012 sustained response occurs in about 40–50% in people with HCV genotype 1 given 48 weeks of treatment.[5] A sustained response is seen in 70–80% of people with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 with 24 weeks of treatment.[5] A sustained response occurs about 65% in those with genotype 4 after 48 weeks of treatment. The evidence for treatment in genotype 6 disease is sparse and what evidence there is supports 48 weeks of treatment at the same doses used for genotype 1 disease.[106]

Epidemiology

It is estimated that 143 million people (2%) of people globally are living with chronic hepatitis C.[6] About 3–4 million people are infected per year, and more than 350,000 people die yearly from hepatitis C-related diseases.[107] During 2010 it is estimated that 16,000 people died from acute infections while 196,000 deaths occurred from liver cancer secondary to the infection.[108] Rates have increased substantially in the 20th century due to a combination of intravenous drug abuse and reused but poorly sterilized medical equipment.[25]

Rates are high (>3.5% population infected) in Central and East Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, they are intermediate (1.5%-3.5%) in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Andean, Central and Southern Latin America, Caribbean, Oceania, Australasia and Central, Eastern and Western Europe; and they are low (<1.5%) in Asia-Pacific, Tropical Latin America and North America.[109]

Among those chronically infected, the risk of cirrhosis after 20 years varies between studies but has been estimated at ~10–15% for men and ~1–5% for women. The reason for this difference is not known. Once cirrhosis is established, the rate of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is ~1–4% per year.[110] Rates of new infections have decreased in the Western world since the 1990s due to improved screening of blood before transfusion.[28]

In the United States, about 2% of people have chronic hepatitis C.[15] In 2014, an estimated 30,500 new acute hepatitis C cases occurred (0.7 per 100,000 population), an increase from 2010–2012.[111] The number of deaths from hepatitis C has increased to 15,800 in 2008[112] having overtaken HIV/AIDS as a cause of death in the USA in 2007.[113] In 2014 it was the single greatest cause of infectious death in the United States.[114] This mortality rate is expected to increase, as those infected by transfusion before HCV testing become apparent.[115] In Europe the percentage of people with chronic infections has been estimated to be between 0.13 and 3.26%.[116]

In England about 160,000 people are chronically infected.[117] Between 2006 and 2011 28,000, about 3%, received treatment.[117] About half of people using a needle exchange in London in 2017/8 tested positive for hepatitis C of which half were unaware of they had it.[118]

The total number of people with this infection is higher in some countries in Africa and Asia.[119] Countries with particularly high rates of infection include Egypt (22%), Pakistan (4.8%) and China (3.2%).[107] It is believed that the high prevalence in Egypt is linked to a now-discontinued mass-treatment campaign for schistosomiasis, using improperly sterilized glass syringes.[25]

History

In the mid-1970s, Harvey J. Alter, Chief of the Infectious Disease Section in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, and his research team demonstrated how most post-transfusion hepatitis cases were not due to hepatitis A or B viruses. Despite this discovery, international research efforts to identify the virus, initially called non-A, non-B hepatitis (NANBH), failed for the next decade. In 1987, Michael Houghton, Qui-Lim Choo, and George Kuo at Chiron Corporation, collaborating with Daniel W. Bradley at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, used a novel molecular cloning approach to identify the unknown organism and develop a diagnostic test.[120] In 1988, Alter confirmed the virus by verifying its presence in a panel of NANBH specimens. In April 1989, the discovery of HCV was published in two articles in the journal Science.[121][122] The discovery led to significant improvements in diagnosis and improved antiviral treatment.[9][120] In 2000, Drs. Alter and Houghton were honored with the Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research for 'pioneering work leading to the discovery of the virus that causes hepatitis C and the development of screening methods that reduced the risk of blood transfusion-associated hepatitis in the U.S. from 30% in 1970 to virtually zero in 2000.'[123]

Chiron filed for several patents on the virus and its diagnosis.[124] A competing patent application by the CDC was dropped in 1990 after Chiron paid $1.9 million to the CDC and $337,500 to Bradley. In 1994, Bradley sued Chiron, seeking to invalidate the patent, have himself included as a coinventor, and receive damages and royalty income. He dropped the suit in 1998 after losing before an appeals court.[125]

Society and culture

World Hepatitis Day, held on July 28, is coordinated by the World Hepatitis Alliance.[126] The economic costs of hepatitis C are significant both to the individual and to society. In the United States the average lifetime cost of the disease was estimated at 33,407 USD in 2003[127] with the cost of a liver transplant as of 2011 costing approximately 200,000 USD.[128] In Canada the cost of a course of antiviral treatment is as high as 30,000 CAD in 2003,[129] while the United States costs are between 9,200 and 17,600 in 1998 USD.[127] In many areas of the world, people are unable to afford treatment with antivirals as they either lack insurance coverage or the insurance they have will not pay for antivirals.[130] In the English National Health Service treatment rates for hepatitis C are higher among wealthier groups per 2010–2012 data.[117] Spanish anaesthetist Juan Maeso infected 275 patients between 1988 and 1997 as he used the same needles to give both himself and the patients opioids.[131] For this he was jailed.[132]

Special populations

Children and pregnancy

Compared with adults, infection in children is much less well understood. Worldwide the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in pregnant women and children has been estimated to 1–8% and 0.05–5% respectively.[133] The vertical transmission rate has been estimated to be 3–5% and there is a high rate of spontaneous clearance (25–50%) in the children. Higher rates have been reported for both vertical transmission (18%, 6–36% and 41%).[134][135] and prevalence in children (15%).[136]

In developed countries transmission around the time of birth is now the leading cause of HCV infection. In the absence of virus in the mother's blood transmission seems to be rare.[135] Factors associated with an increased rate of infection include membrane rupture of longer than 6 hours before delivery and procedures exposing the infant to maternal blood.[137] Cesarean sections are not recommended. Breastfeeding is considered safe if the nipples are not damaged. Infection around the time of birth in one child does not increase the risk in a subsequent pregnancy. All genotypes appear to have the same risk of transmission.

HCV infection is frequently found in children who have previously been presumed to have non-A, non-B hepatitis and cryptogenic liver disease.[138] The presentation in childhood may be asymptomatic or with elevated liver function tests.[139] While infection is commonly asymptomatic both cirrhosis with liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma may occur in childhood.

Immunosuppressed

The rate of hepatitis C in immunosuppressed people is higher. This is particularly true in those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, recipients of organ transplants, and those with hypogammaglobulinemia.[140] Infection in these people is associated with an unusually rapid progression to cirrhosis. People with stable HIV who never received medication for HCV, may be treated with a combination of peginterferon plus ribavirin with caution to the possible side effects.[141]

Research

As of 2011, there are about one hundred medications in development for hepatitis C.[128] These include vaccines to treat hepatitis, immunomodulators, and cyclophilin inhibitors, among others.[142] These potential new treatments have come about due to a better understanding of the hepatitis C virus.[143] There are a number of vaccines under development and some have shown encouraging results.[78]

The combination of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir in one trial (reported in 2015) resulted in cure rates of 99%.[144] More studies are needed to investigate the role of the preventative antiviral medication against HCV recurrence after transplantation.[145]

Animal models

One barrier to finding treatments for hepatitis C is the lack of a suitable animal model. Despite moderate success, current research highlights the need for pre-clinical testing in mammalian systems such as mouse, particularly for the development of vaccines in poorer communities. Currently, chimpanzees remain the available living system to study, yet their use has ethical concerns and regulatory restrictions. While scientists have made use of human cell culture systems such as hepatocytes, questions have been raised about their accuracy in reflecting the body's response to infection.[146]

One aspect of hepatitis research is to reproduce infections in mammalian models. A strategy is to introduce liver tissues from humans into mice, a technique known as xenotransplantation. This is done by generating chimeric mice, and exposing the mice HCV infection. This engineering process is known to create humanized mice, and provide opportunities to study hepatitis C within the 3D architectural design of the liver and evaluating antiviral compounds.[146] Alternatively, generating inbred mice with susceptibility to HCV would simplify the process of studying mouse models.

References

- ^ abcdefghijklmnopqrs'Hepatitis C FAQs for Health Professionals'. CDC. January 8, 2016. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ abcRyan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 551–2. ISBN978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ abcMaheshwari, A; Thuluvath, PJ (February 2010). 'Management of acute hepatitis C'. Clinics in Liver Disease. 14 (1): 169–76, x. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.007. PMID20123448.

- ^ abcdefghijk'Hepatitis C Fact sheet N°164'. WHO. July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ abcdefghijklmnRosen, HR (2011-06-23). 'Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection'. The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (25): 2429–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. PMID21696309.

- ^ abcGBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). 'Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015'. Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC5055577. PMID27733282.

- ^ abGBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). 'Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015'. Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC5388903. PMID27733281.

- ^'Viral Hepatitis: A through E and Beyond'. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. April 2012. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ abcWebster, Daniel P; Klenerman, Paul; Dusheiko, Geoffrey M (2015). 'Hepatitis C'. The Lancet. 385 (9973): 1124–1135. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62401-6. ISSN0140-6736. PMC4878852. PMID25687730.

- ^ abcdefgKim, A (September 2016). 'Hepatitis C Virus'. Annals of Internal Medicine (Review). 165 (5): ITC33–ITC48. doi:10.7326/AITC201609060. PMID27595226.

- ^Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (22 August 2015). 'Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013'. Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC4561509. PMID26063472.

- ^Houghton M (November 2009). 'The long and winding road leading to the identification of the hepatitis C virus'. Journal of Hepatology. 51 (5): 939–48. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.08.004. PMID19781804.

- ^Shors, Teri (2011-11-08). Understanding viruses (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 535. ISBN978-0-7637-8553-6. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15.

- ^Maheshwari, A; Ray S; Thuluvath PJ (2008-07-26). 'Acute hepatitis C'. Lancet. 372 (9635): 321–32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61116-2. PMID18657711.

- ^ abcdefghijklmnopqrsWilkins, T; Malcolm JK; Raina D; Schade RR (2010-06-01). 'Hepatitis C: diagnosis and treatment'(PDF). American Family Physician. 81 (11): 1351–7. PMID20521755. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2013-05-21.

- ^Bailey, Caitlin (Nov 2010). 'Hepatic Failure: An Evidence-Based Approach In The Emergency Department'. Emergency Medicine Practice. 12 (4). Archived from the original on 2012-11-21.

- ^ abcdeChronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. 2011. p. 4. ISBN978-1-4614-1191-8. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17.

- ^ abcdNelson, PK; Mathers BM; Cowie B; Hagan H; Des Jarlais D; Horyniak D; Degenhardt L (2011-08-13). 'Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews'. Lancet. 378 (9791): 571–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. PMC3285467. PMID21802134.

- ^ abcdChronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. 2011. pp. 103–104. ISBN978-1-4614-1191-8. Archived from the original on 2016-05-29.

- ^ abcdefgRay, Stuart C.; Thomas, David L. (2009). 'Chapter 154: Hepatitis C'. In Mandell, Gerald L.; Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael (eds.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN978-0-443-06839-3.

- ^Forton, DM; Allsop, JM; Cox, IJ; Hamilton, G; Wesnes, K; Thomas, HC; Taylor-Robinson, SD (October 2005). 'A review of cognitive impairment and cerebral metabolite abnormalities in patients with hepatitis C infection'. AIDS. 19 (Suppl 3): S53–63. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000192071.72948.77. PMID16251829.

- ^ abcNicot, F (2004). 'Chapter 19. Liver biopsy in modern medicine.'. Occult hepatitis C virus infection: Where are we now?. ISBN978-953-307-883-0.

- ^ abEl-Zayadi, AR (2008-07-14). 'Hepatic steatosis: a benign disease or a silent killer'. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (26): 4120–6. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4120. PMC2725370. PMID18636654.

- ^Paradis, V; Bedossa, P (December 2008). 'Definition and natural history of metabolic steatosis: histology and cellular aspects'. Diabetes & Metabolism. 34 (6 Pt 2): 638–42. doi:10.1016/S1262-3636(08)74598-1. PMID19195624.

- ^ abcdefghijAlter, MJ (2007-05-07). 'Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection'. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (17): 2436–41. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. PMC4146761. PMID17552026.[permanent dead link]

- ^Mueller, S; Millonig G; Seitz HK (2009-07-28). 'Alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C: a frequently underestimated combination'(PDF). World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (28): 3462–71. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.3462. PMC2715970. PMID19630099.[permanent dead link]

- ^Fattovich, G; Stroffolini, T; Zagni, I; Donato, F (November 2004). 'Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors'. Gastroenterology. 127 (5 Suppl 1): S35–50. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.014. PMID15508101.

- ^ abcdeOzaras, R; Tahan, V (April 2009). 'Acute hepatitis C: prevention and treatment'. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 7 (3): 351–61. doi:10.1586/eri.09.8. PMID19344247.

- ^Zaltron, S; Spinetti, A; Biasi, L; Baiguera, C; Castelli, F (2012). 'Chronic HCV infection: epidemiological and clinical relevance'. BMC Infectious Diseases. 12 Suppl 2: S2. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-S2-S2. PMC3495628. PMID23173556.

- ^Dammacco F, Sansonno D (September 12, 2013). 'Review Article: Therapy for Hepatitis C Virus–Related Cryoglobulinemic Vasculitis'. N Engl J Med. 369 (11): 1035–1045. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1208642. PMID24024840.

- ^Iannuzzella, F; Vaglio, A; Garini, G (May 2010). 'Management of hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia'. Am. J. Med. 123 (5): 400–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.038. PMID20399313.

- ^Zignego, AL; Ferri, C; Pileri, SA; et al. (January 2007). 'Extrahepatic manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus infection: a general overview and guidelines for a clinical approach'. Digestive and Liver Disease. 39 (1): 2–17. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.06.008. PMID16884964.

- ^Ko, HM; Hernandez-Prera, JC; Zhu, H; Dikman, SH; Sidhu, HK; Ward, SC; Thung, SN (2012). 'Morphologic features of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection'. Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/740138. PMC3420144. PMID22919404.

- ^Dammacco, F; Sansonno, D; Piccoli, C; Racanelli, V; D'Amore, FP; Lauletta, G (2000). 'The lymphoid system in hepatitis C virus infection: autoimmunity, mixed cryoglobulinemia, and Overt B-cell malignancy'. Seminars in Liver Disease. 20 (2): 143–57. doi:10.1055/s-2000-9613. PMID10946420.

- ^Lee, MR; Shumack, S (November 2005). 'Prurigo nodularis: a review'. The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 46 (4): 211–18, quiz 219–20. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00187.x. PMID16197418.

- ^Matsumori, A (2006). Role of hepatitis C virus in cardiomyopathies. Ernst Schering Research Foundation Workshop. 55. pp. 99–120. doi:10.1007/3-540-30822-9_7. ISBN978-3-540-23971-0. PMID16329660.

- ^Monaco, S; Ferrari, S; Gajofatto, A; Zanusso, G; Mariotto, S (2012). 'HCV-related nervous system disorders'. Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/236148. PMC3414089. PMID22899946.

- ^Xu, JH; Fu, JJ; Wang, XL; Zhu, JY; Ye, XH; Chen, SD (2013-07-14). 'Hepatitis B or C viral infection and risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies'. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (26): 4234–41. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4234. PMC3710428. PMID23864789.

- ^Lodi, G.; Porter, S.R; Scully, C. (1998-07-01). 'Hepatitis C virus infection: Review and implications for the dentist'. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 86 (1): 8–22. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90143-3. ISSN1079-2104.

- ^Carrozzo, M.; Gandolfo, S. (2003-03-01). 'Oral Diseases Possibly Associated with Hepatitis C Virus'. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine. 14 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1177/154411130301400205. ISSN1045-4411.

- ^Little, James W.; Falace, Donald A.; Miller, Craig; Rhodus, Nelson L. (2013). Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. p. 151. ISBN9780323080286.

- ^Sugden, PB; Cameron, B; Bull, R; White, PA; Lloyd, AR (September 2012). 'Occult infection with hepatitis C virus: friend or foe?'. Immunology and Cell Biology. 90 (8): 763–73. doi:10.1038/icb.2012.20. PMID22546735.

- ^Carreño, V (2006-11-21). 'Occult hepatitis C virus infection: a new form of hepatitis C.'World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (43): 6922–5. doi:10.3748/wjg.12.6922. PMC4087333. PMID17109511.

- ^ abCarreño García, V; Nebreda, JB; Aguilar, IC; Quiroga Estévez, JA (March 2011). '[Occult hepatitis C virus infection]'. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 29 Suppl 3: 14–9. doi:10.1016/S0213-005X(11)70022-2. PMID21458706.

- ^Pham, TN; Coffin, CS; Michalak, TI (April 2010). 'Occult hepatitis C virus infection: what does it mean?'. Liver International. 30 (4): 502–11. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02193.x. PMID20070513.

- ^Carreño, V; Bartolomé, J; Castillo, I; Quiroga, JA (2012-06-21). 'New perspectives in occult hepatitis C virus infection'. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (23): 2887–94. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i23.2887. PMC3380315. PMID22736911.

- ^Carreño, V; Bartolomé, J; Castillo, I; Quiroga, JA (May–June 2008). 'Occult hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections'. Reviews in Medical Virology. 18 (3): 139–57. doi:10.1002/rmv.569. PMID18265423.

- ^Scott, JD; Gretch, DR (2007-02-21). 'Molecular diagnostics of hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review'. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 297 (7): 724–32. doi:10.1001/jama.297.7.724. PMID17312292.

- ^ abRobinson, JL (July 4, 2008). 'Vertical transmission of the hepatitis C virus: Current knowledge and issues'. Paediatr Child Health. 13 (6): 529–534. doi:10.1093/pch/13.6.529. PMC2532905. PMID19436425.

- ^Nakano, T; Lau, GM; Lau, GM; et al. (December 2011). 'An updated analysis of hepatitis C virus genotypes and subtypes based on the complete coding region'. Liver Int. 32 (2): 339–45. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02684.x. PMID22142261.

- ^ abLerat, H; Hollinger, FB (2004-01-01). 'Hepatitis C virus (HCV) occult infection or occult HCV RNA detection?'. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 189 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1086/380203. PMID14702146.

- ^Pockros, Paul (2011). Novel and Combination Therapies for Hepatitis C Virus, An Issue of Clinics in Liver Disease. p. 47. ISBN978-1-4557-7198-1. Archived from the original on 2016-05-21.

- ^Zignego, AL; Giannini, C; Gragnani, L; Piluso, A; Fognani, E (2012-08-03). 'Hepatitis C virus infection in the immunocompromised host: a complex scenario with variable clinical impact'. Journal of Translational Medicine. 10 (1): 158. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-10-158. PMC3441205. PMID22863056.

- ^ abcdePondé, RA (February 2011). 'Hidden hazards of HCV transmission'. Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 200 (1): 7–11. doi:10.1007/s00430-010-0159-9. PMID20461405.

- ^ abXia, X; Luo J; Bai J; Yu R (October 2008). 'Epidemiology of HCV infection among injection drug users in China: systematic review and meta-analysis'. Public Health. 122 (10): 990–1003. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.014. PMID18486955.

- ^Imperial, JC (June 2010). 'Chronic hepatitis C in the state prison system: insights into the problems and possible solutions'. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 4 (3): 355–64. doi:10.1586/egh.10.26. PMID20528122.

- ^Vescio, MF; Longo B; Babudieri S; Starnini G; Carbonara S; Rezza G; Monarca R (April 2008). 'Correlates of hepatitis C virus seropositivity in prison inmates: a meta-analysis'. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 62 (4): 305–13. doi:10.1136/jech.2006.051599. PMID18339822.

- ^Moyer, VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (3 September 2013). 'Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement'. Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (5): 349–57. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. PMID23798026.

- ^ abMarx, John (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1154. ISBN978-0-323-05472-0.

- ^Day RA, Paul P, Williams B, et al. (November 2009). Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of Canadian medical-surgical nursing (Canadian 2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1237. ISBN978-0-7817-9989-8. Archived from the original on 2016-04-25.

- ^'Highest Rates of Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Found in Egypt'. Al Bawaaba. 2010-08-09. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^Tohme RA, Holmberg SD (June 2010). 'Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission?'. Hepatology. 52 (4): 1497–505. doi:10.1002/hep.23808. PMID20635398.

- ^'Hepatitis C Group Education Class'. United States Department of Veteran Affairs. Archived from the original on 2011-11-09.

- ^ abcdefJafari, S; Copes R; Baharlou S; Etminan M; Buxton J (November 2010). 'Tattooing and the risk of transmission of hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis'(PDF). International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 14 (11): e928–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2010.03.019. PMID20678951. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2012-04-26.

- ^'Hepatitis C'(PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived(PDF) from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^Lock G, Dirscherl M, Obermeier F, et al. (September 2006). 'Hepatitis C — contamination of toothbrushes: myth or reality?'. J. Viral Hepat. 13 (9): 571–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00735.x. PMID16907842.

- ^ abc'Hepatitis C FAQs for Health Professionals'. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^Wong T, Lee SS (February 2006). 'Hepatitis C: a review for primary care physicians'. CMAJ. 174 (5): 649–59. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1030034. PMC1389829. PMID16505462.

- ^ abLam, NC; Gotsch, PB; Langan, RC (2010-11-15). 'Caring for pregnant women and newborns with hepatitis B or C'(PDF). American Family Physician. 82 (10): 1225–9. PMID21121533. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2013-05-21.

- ^Mast EE (2004). Mother-to-infant hepatitis C virus transmission and breastfeeding. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 554. pp. 211–6. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_18. ISBN978-1-4419-3461-1. PMID15384578.

- ^Shivkumar, S; Peeling, R; Jafari, Y; Joseph, L; Pant Pai, N (2012-10-16). 'Accuracy of Rapid and Point-of-Care Screening Tests for Hepatitis C: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis'. Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (8): 558–66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00006. PMID23070489.

- ^ abAustria, A; Wu, GY (28 June 2018). 'Occult Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Review'. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology. 6 (2): 155–160. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2017.00053. PMC6018308. PMID29951360.

- ^Moyer, VA (on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force) (2013-06-25). 'Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement'. Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (5): 349–57. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. PMID23798026.

- ^Moyer, VA (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force) (2013-09-03). 'Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement'. Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (5): 349–57. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. PMID23798026.

- ^Senadhi, V (July 2011). 'A paradigm shift in the outpatient approach to liver function tests'. Southern Medical Journal. 104 (7): 521–5. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31821e8ff5. PMID21886053.

- ^Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. (August 2012). 'Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965'. MMWR Recomm Rep. 61 (RR-4): 1–32. PMID22895429.

- ^Shah, Hemant; Bilodeau, Marc; Burak, Kelly W.; Cooper, Curtis; Klein, Marina; Ramji, Alnoor; Smyth, Dan; Feld, Jordan J. (4 June 2018). 'The management of chronic hepatitis C: 2018 guideline update from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver'. CMAJ. 190 (22): E677–E687. doi:10.1503/cmaj.170453. ISSN0820-3946. PMC5988519. PMID29866893.

- ^ abAbdelwahab, KS; Ahmed Said, ZN (14 January 2016). 'Status of hepatitis C virus vaccination: Recent update'. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (2): 862–73. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.862. PMC4716084. PMID26811632.

- ^Hagan, H; Pouget, ER; Des Jarlais, DC (2011-07-01). 'A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs'. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (1): 74–83. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir196. PMC3105033. PMID21628661. Archived from the original on 2014-10-31.

- ^ abAASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance, Panel (September 2015). 'Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus'. Hepatology. 62 (3): 932–54. doi:10.1002/hep.27950. PMID26111063.

- ^ ab'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C'(PDF). 12 April 2017. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2017-07-10. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^Jakobsen, JC; Nielsen, EE; Feinberg, J; Katakam, KK; Fobian, K; Hauser, G; Poropat, G; Djurisic, S; Weiss, KH; Bjelakovic, M; Bjelakovic, G; Klingenberg, SL; Liu, JP; Nikolova, D; Koretz, RL; Gluud, C (18 September 2017). 'Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C.'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD012143. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012143.pub3. PMID28922704.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 1a Without Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 1a With Compensated Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 1b Without Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 1b With Compensated Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 2 Without Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 2 With Compensated Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 3 Without Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 3 With Compensated Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 4 Without Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 4 With Compensated Cirrhosis'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^'HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: Treatment-Naive Genotype 5 or 6'. www.hcvguidelines.org. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^Commissioner, Office of the (18 July 2017). 'Press Announcements - FDA approves Vosevi for Hepatitis C'. www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^Liang, TJ; Ghany, MG (May 16, 2013). 'Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection'. The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (20): 1907–17. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1213651. PMC3893124. PMID23675659.

- ^Mücke, Marcus M; Backus, Lisa I; Mücke, Victoria T; Coppola, Nicola; Preda, Carmen M; Yeh, Ming-Lun; Tang, Lydia S Y; Belperio, Pamela S; Wilson, Eleanor M; Yu, Ming-Lung; Zeuzem, Stefan; Herrmann, Eva; Vermehren, Johannes (January 2018). 'Hepatitis B virus reactivation during direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis'. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 3 (3): 172–180. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30002-5. PMID29371017.

- ^Sanders, Mick (2011). Mosby's Paramedic Textbook. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 839. ISBN978-0-323-07275-5. Archived from the original on 2016-05-11.

- ^Ciria R, Pleguezuelo M, Khorsandi SE, et al. (May 2013). 'Strategies to reduce hepatitis C virus recurrence after liver transplantation'. World J Hepatol. 5 (5): 237–50. doi:10.4254/wjh.v5.i5.237. PMC3664282. PMID23717735.

- ^Coilly A, Roche B, Samuel D (February 2013). 'Current management and perspectives for HCV recurrence after liver transplantation'. Liver Int. 33 Suppl 1: 56–62. doi:10.1111/liv.12062. PMID23286847.

- ^Gurusamy, KS; Tsochatzis, E; Toon, CD; Xirouchakis, E; Burroughs, AK; Davidson, BR (4 December 2013). 'Antiviral interventions for liver transplant patients with recurrent graft infection due to hepatitis C virus'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD006803. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006803.pub4. PMID24307460.

- ^ abHepatitis C and CAM: What the Science SaysArchived 2011-03-20 at the Wayback Machine. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). March 2011. (Retrieved 7 March 2011)

- ^Liu, J; Manheimer E; Tsutani K; Gluud C (March 2003). 'Medicinal herbs for hepatitis C virus infection: a Cochrane hepatobiliary systematic review of randomized trials'. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 98 (3): 538–44. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07298.x. PMID12650784.

- ^Rambaldi, A; Jacobs, BP; Gluud, C (17 October 2007). 'Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003620. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003620.pub3. PMID17943794.

- ^Helms, Richard A.; Quan, David J., eds. (2006). Textbook of Therapeutics: Drug and Disease Management (8. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa. [u.a.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1340. ISBN978-0-7817-5734-8. Archived from the original on 5 December 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y (March 2013). 'Eradication of Hepatitis C Virus Infection and the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-analysis of Observational Studies'. Annals of Internal Medicine. 158 (5 Pt 1): 329–37. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005. PMID23460056.

- ^Fung J, Lai CL, Hung I, et al. (September 2008). 'Chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 6 infection: response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin'. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (6): 808–12. doi:10.1086/591252. PMID18657036. Archived from the original on 2015-11-04.

- ^ ab'Hepatitis C'. World Health Organization (WHO). June 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ^Lozano, R (2012-12-15). 'Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010'. Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID23245604.

- ^Mohd Hanafiah, K; Groeger, J; Flaxman, AD; Wiersma, ST (April 2013). 'Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence'. Hepatology. 57 (4): 1333–42. doi:10.1002/hep.26141. PMID23172780.

- ^Yu ML; Chuang WL (March 2009). 'Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West'. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24 (3): 336–45. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05789.x. PMID19335784.

- ^'U.S. 2014 Surveillance Data for Viral Hepatitis, Statistics & Surveillance, Division of Viral Hepatitis'. CDC. Archived from the original on 2016-08-08. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ^Table 4.5. 'Number and rate of deaths with hepatitis C listed as a cause of death, by demographic characteristic and year — United States, 2004–2008'. Viral Hepatitis on the CDC web site. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^'Hepatitis Death Rate Creeps past AIDS'. New York Times. 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^'Hepatitis C Kills More Americans than Any Other Infectious Disease'. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^Blatt, L. M.; Tong, M. (2004). Colacino, J. M.; Heinz, B. A. (eds.). Hepatitis prevention and treatment. Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 32. ISBN978-3-7643-5956-0. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24.

- ^Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC, Roudot-Thoraval F (March 2013). 'The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data'. J. Hepatol. 58 (3): 593–608. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.005. PMID23419824.

- ^ abc'Commissioning supplement: Health inequalities tell a tale of data neglect'. Health Service Journal. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^'More than half of patients using needle exchange pilot tested positive for Hepatitis C'. Pharmaceutical Journal. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^Holmberg, Scott (2011-05-12). Brunette, Gary W.; Kozarsky, Phyllis E.; Magill, Alan J.; Shlim, David R.; Whatley, Amanda D. (eds.). CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN978-0-19-976901-8. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19.

- ^ abBoyer, JL (2001). Liver cirrhosis and its development: proceedings of the Falk Symposium 115. Springer. pp. 344. ISBN978-0-7923-8760-2.

- ^Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M (April 1989). 'Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome'(PDF). Science. 244 (4902): 359–62. CiteSeerX10.1.1.469.3592. doi:10.1126/science.2523562. PMID2523562.

- ^Kuo G, Choo QL, Alter HJ, et al. (April 1989). 'An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis'. Science. 244 (4902): 362–4. doi:10.1126/science.2496467. PMID2496467.

- ^'2000 Winners Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research'. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved 2006-04-21.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ^EP patent 0318216, Houghton, M; Choo, Q-L & Kuo, G, 'NANBV diagnostics', issued 1989-05-31, assigned to Chiron

- ^Wilken. 'United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit'. United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^Eurosurveillance editorial team (2011-07-28). 'World Hepatitis Day 2011'(PDF). Eurosurveillance. 16 (30). PMID21813077. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2011-11-25.

- ^ abWong, JB (2006). 'Hepatitis C: cost of illness and considerations for the economic evaluation of antiviral therapies'. PharmacoEconomics. 24 (7): 661–72. doi:10.2165/00019053-200624070-00005. PMID16802842.

- ^ abEl Khoury, AC; Klimack, WK; Wallace, C; Razavi, H (1 December 2011). 'Economic burden of hepatitis C-associated diseases in the United States'. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 19 (3): 153–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01563.x. PMID22329369.

- ^'Hepatitis C Prevention, Support and Research ProgramHealth Canada'. Public Health Agency of Canada. Nov 2003. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^Thomas, Howard; Lemon, Stanley; Zuckerman, Arie, eds. (2008). Viral Hepatitis (3rd ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. p. 532. ISBN978-1-4051-4388-2. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17.

- ^'Spanish Anesthetist Infected Patients'. The Washington Post. 15 May 2007. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^'Spanish Hep C anaesthetist jailed'. BBC. 15 May 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^Arshad M, El-Kamary SS, Jhaveri R (April 2011). 'Hepatitis C virus infection during pregnancy and the newborn period—are they opportunities for treatment?'. J. Viral Hepat. 18 (4): 229–36. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01413.x. PMID21392169.

- ^Hunt CM, Carson KL, Sharara AI (May 1997). 'Hepatitis C in pregnancy'. Obstet Gynecol. 89 (5 Pt 2): 883–90. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(97)81434-2. PMID9166361.

- ^ abThomas SL, Newell ML, Peckham CS, Ades AE, Hall AJ (February 1998). 'A review of hepatitis C virus (HCV) vertical transmission: risks of transmission to infants born to mothers with and without HCV viraemia or human immunodeficiency virus infection'. Int J Epidemiol. 27 (1): 108–17. doi:10.1093/ije/27.1.108. PMID9563703.

- ^Fischler B (June 2007). 'Hepatitis C virus infection'. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 12 (3): 168–73. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.008. PMID17320495.

- ^Indolfi G, Resti M (May 2009). 'Perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus infection'. J. Med. Virol. 81 (5): 836–43. doi:10.1002/jmv.21437. PMID19319981.

- ^González-Peralta RP (November 1997). 'Hepatitis C virus infection in pediatric patients'. Clin Liver Dis. 1 (3): 691–705, ix. doi:10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70329-9. PMID15560066.

- ^Suskind DL, Rosenthal P (February 2004). 'Chronic viral hepatitis'. Adolesc Med Clin. 15 (1): 145–58, x–xi. doi:10.1016/j.admecli.2003.11.001. PMID15272262.

- ^Einav S, Koziel MJ (June 2002). 'Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus in the immunosuppressed host'. Transpl Infect Dis. 4 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3062.2002.t01-2-02001.x. PMID12220245.

- ^Iorio, A; Marchesini, E; Awad, T; Gluud, LL (20 January 2010). 'Antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C in patients with human immunodeficiency virus'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004888. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004888.pub2. PMID20091566.

- ^Ahn, J; Flamm, SL (August 2011). 'Hepatitis C therapy: other players in the game'. Clinics in Liver Disease. 15 (3): 641–56. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2011.05.008. PMID21867942.

- ^Vermehren, J; Sarrazin, C (February 2011). 'New HCV therapies on the horizon'. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 17 (2): 122–34. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03430.x. PMID21087349.

- ^Feld, Jordan J.; Jacobson, Ira M.; Hézode, Christophe; Asselah, Tarik; Ruane, Peter J.; Gruener, Norbert; Abergel, Armand; Mangia, Alessandra; Lai, Ching-Lung; Chan, Henry L.Y.; Mazzotta, Francesco; Moreno, Christophe; Yoshida, Eric; Shafran, Stephen D.; Towner, William J.; Tran, Tram T.; McNally, John; Osinusi, Anu; Svarovskaia, Evguenia; Zhu, Yanni; Brainard, Diana M.; McHutchison, John G.; Agarwal, Kosh; Zeuzem, Stefan (16 November 2015). 'Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV Genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 Infection'. New England Journal of Medicine. 373 (27): 2599–2607. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1512610. PMID26571066.

- ^Gurusamy, KS; Tsochatzis, E; Toon, CD; Davidson, BR; Burroughs, AK (2 December 2013). 'Antiviral prophylaxis for the prevention of chronic hepatitis C virus in patients undergoing liver transplantation'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD006573. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006573.pub3. PMID24297303.

- ^ abSandmann, L; Ploss, A (2013-01-05). 'Barriers of hepatitis C virus interspecies transmission'. Virology. 435 (1): 70–80. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.044. PMC3523278. PMID23217617.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hepatitis C. |

- Hepatitis C at Curlie

- 'Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C'. www.hcvguidelines.org. IDSA/AASLD. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

| Hepatitis B | |

|---|---|

| Electron micrograph of hepatitis B virus | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | None, yellowish skin, tiredness, dark urine, abdominal pain[1] |

| Complications | Cirrhosis, liver cancer[2] |

| Usual onset | Symptoms may take up to 6 months to appear[1] |

| Duration | Short or long term[3] |

| Causes | Hepatitis B virus spread by some body fluids[1] |

| Risk factors | Intravenous drug use, sexual intercourse, dialysis, living with an infected person[1][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests[1] |

| Prevention | Hepatitis B vaccine[1] |

| Treatment | Antiviral medication (tenofovir, interferon), liver transplantation[1] |

| Frequency | 356 million (2015)[3] |

| Deaths | 65,400 direct (2015), >750,000 (total)[1][5] |

Hepatitis B is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) that affects the liver.[1] It can cause both acute and chronic infections.[1] Many people have no symptoms during the initial infection.[1] Some develop a rapid onset of sickness with vomiting, yellowish skin, tiredness, dark urine and abdominal pain.[1] Often these symptoms last a few weeks and rarely does the initial infection result in death.[1][6] It may take 30 to 180 days for symptoms to begin.[1] In those who get infected around the time of birth 90% develop chronic hepatitis B while less than 10% of those infected after the age of five do.[4] Most of those with chronic disease have no symptoms; however, cirrhosis and liver cancer may eventually develop.[2] These complications result in the death of 15 to 25% of those with chronic disease.[1]

The virus is transmitted by exposure to infectious blood or body fluids.[1]Infection around the time of birth or from contact with other people's blood during childhood is the most frequent method by which hepatitis B is acquired in areas where the disease is common.[1] In areas where the disease is rare, intravenous drug use and sexual intercourse are the most frequent routes of infection.[1] Other risk factors include working in healthcare, blood transfusions, dialysis, living with an infected person, travel in countries where the infection rate is high, and living in an institution.[1][4]Tattooing and acupuncture led to a significant number of cases in the 1980s; however, this has become less common with improved sterility.[7] The hepatitis B viruses cannot be spread by holding hands, sharing eating utensils, kissing, hugging, coughing, sneezing, or breastfeeding.[4] The infection can be diagnosed 30 to 60 days after exposure.[1] The diagnosis is usually confirmed by testing the blood for parts of the virus and for antibodies against the virus.[1] It is one of five main hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E.[8]

The infection has been preventable by vaccination since 1982.[1][9] Vaccination is recommended by the World Health Organization in the first day of life if possible.[1] Two or three more doses are required at a later time for full effect.[1] This vaccine works about 95% of the time.[1] About 180 countries gave the vaccine as part of national programs as of 2006.[10] It is also recommended that all blood be tested for hepatitis B before transfusion, and that condoms be used to prevent infection.[1] During an initial infection, care is based on the symptoms that a person has.[1] In those who develop chronic disease, antiviral medication such as tenofovir or interferon may be useful; however, these drugs are expensive.[1]Liver transplantation is sometimes used for cirrhosis.[1]

About a third of the world population has been infected at one point in their lives, including 343 million who have chronic infections.[1][3][11] Another 129 million new infections occurred in 2013.[12] Over 750,000 people die of hepatitis B each year.[1] About 300,000 of these are due to liver cancer.[13] The disease is now only common in East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa where between 5 and 10% of adults are chronically infected.[1] Rates in Europe and North America are less than 1%.[1] It was originally known as 'serum hepatitis'.[14] Research is looking to create foods that contain HBV vaccine.[15] The disease may affect other great apes as well.[16]

- 2Cause

- 2.2Virology

- 5Prevention

- 7Prognosis

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Acute infection with hepatitis B virus is associated with acute viral hepatitis, an illness that begins with general ill-health, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, body aches, mild fever, and dark urine, and then progresses to development of jaundice. It has been noted that itchy skin has been an indication as a possible symptom of all hepatitis virus types. The illness lasts for a few weeks and then gradually improves in most affected people. A few people may have a more severe form of liver disease known as fulminant hepatic failure and may die as a result. The infection may be entirely asymptomatic and may go unrecognized.[17]

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus either may be asymptomatic or may be associated with a chronic inflammation of the liver (chronic hepatitis), leading to cirrhosis over a period of several years. This type of infection dramatically increases the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; liver cancer). Across Europe, hepatitis B and C cause approximately 50% of hepatocellular carcinomas.[18][19] Chronic carriers are encouraged to avoid consuming alcohol as it increases their risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer. Hepatitis B virus has been linked to the development of membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN).[20]

Symptoms outside of the liver are present in 1–10% of HBV-infected people and include serum-sickness–like syndrome, acute necrotizing vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa), membranous glomerulonephritis, and papular acrodermatitis of childhood (Gianotti–Crosti syndrome).[21][22] The serum-sickness–like syndrome occurs in the setting of acute hepatitis B, often preceding the onset of jaundice.[23] The clinical features are fever, skin rash, and polyarteritis. The symptoms often subside shortly after the onset of jaundice but can persist throughout the duration of acute hepatitis B.[24] About 30–50% of people with acute necrotizing vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa) are HBV carriers.[25] HBV-associated nephropathy has been described in adults but is more common in children.[26][27] Membranous glomerulonephritis is the most common form.[24] Other immune-mediated hematological disorders, such as essential mixed cryoglobulinemia and aplastic anemia have been described as part of the extrahepatic manifestations of HBV infection, but their association is not as well-defined; therefore, they probably should not be considered etiologically linked to HBV.[24]

Cause[edit]

Transmission[edit]

Transmission of hepatitis B virus results from exposure to infectious blood or body fluids containing blood. It is 50 to 100 times more infectious than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[28] Possible forms of transmission include sexual contact,[29]blood transfusions and transfusion with other human blood products,[30]re-use of contaminated needles and syringes,[31] and vertical transmission from mother to child (MTCT) during childbirth. Without intervention, a mother who is positive for HBsAg has a 20% risk of passing the infection to her offspring at the time of birth. This risk is as high as 90% if the mother is also positive for HBeAg. HBV can be transmitted between family members within households, possibly by contact of nonintact skin or mucous membrane with secretions or saliva containing HBV.[32] However, at least 30% of reported hepatitis B among adults cannot be associated with an identifiable risk factor.[33] Breastfeeding after proper immunoprophylaxis does not appear to contribute to mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) of HBV.[34] The virus may be detected within 30 to 60 days after infection and can persist and develop into chronic hepatitis B. The incubation period of the hepatitis B virus is 75 days on average but can vary from 30 to 180 days.[35]

Virology[edit]

Structure[edit]